NIST engineers are working with scientists from the University of Arizona (Tucson) and Boeing Research & Technology (Seattle, Wash.) to design antennas incorporating metamaterials — materials engineered with novel, often microscopic, structures to produce unusual properties. The new antennas radiate as much as 95 percent of an input radio signal and yet defy normal design parameters. Standard antennas need to be at least half the size of the signal wavelength to operate efficiently; at 300 MHz, for instance, an antenna would need to be half a meter long. The experimental antennas are as small as one-fiftieth of a wavelength and could shrink further.

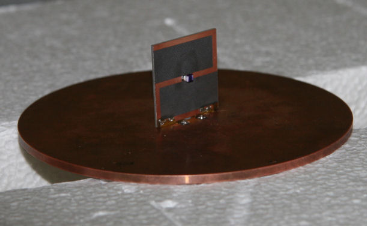

In their latest prototype device,* the research team used a metal wire antenna printed on a small square of copper measuring less than 65 millimeters on a side. The antenna is wired to a signal source. Mounted on the back of the square is a “Z element” that acts as a metamaterial — a Z-shaped strip of copper with an inductor (a device that stores energy magnetically) in the center (see photo).

“The purpose of an antenna is to launch energy into free space,” explains NIST engineer Christopher Holloway, “But the problem with antennas that are very small compared to the wavelength is that most of the signal just gets reflected back to the source. The metamaterial makes the antenna behave as if it were much larger than it really is, because the antenna structure stores energy and re-radiates it.” Conventional antenna designs, Holloway says, achieve a similar effect by adding bulky “matching network” components to boost efficiency, but the metamaterial system can be made much smaller. Even more intriguing, Holloway says, “these metamaterials are much more ‘frequency agile.’ It’s possible we could tune them to work at any frequency we want, on the fly,” to a degree not possible with conventional designs.

The Z antennas were designed at the University of Arizona and fabricated and partially measured at Boeing Research & Technology. The power efficiency measurements were carried out at NIST laboratories in Boulder, Colo. The ongoing research is sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.